The Limited Importance of Intelligence

Why You Are Not Going to Get Paperclipped by the Machine God

Oh, noes! We have developed a chatbot that can say dumb stuff in a slightly glib manner!

Surely an artificial godlike intelligence is right around the corner, waiting to turn us all into a Harlan Ellison short story!

Well, no.

Take a breath.

Let’s think about how intelligence actually works.

If we view intelligence as the ability to derive and construct narratives, we can understand how it helps us, and how it doesn’t.

Because of our intelligence, humanity is indeed godlike compared to animals. If you think from the perspective of, say, deer, we must appear something like Lovecraft’s Elder Gods… alien, unknowable, mysterious, powerful beyond sense and reason.

“Sometimes they kill us from far away with a sound like thunder. Sometimes they help us when we get stuck in one their mysterious barrier things. Sometimes they just stand around flashing and making clicking noises.”

Yes, the reason we have rifles, wire fences, and cameras, and deer don’t, is that we are smarter than deer.

But intelligence doesn’t spontaneously generate power or technology, and intelligent species don’t always beat stupid ones.

From Neanderthals, to beyond

The Neanderthal were replaced by modern humans with lower brain volumes, surviving only as fractional DNA in certain human subraces (which are, by coincidence or not, the smarter ones). Western civilizations with high average IQs are being invaded and outbred by low-IQ third world populations, with the full cooperation of a significant number of high-IQ westerners.

In addition, humanity has existed, probably at close to its current IQ levels, for about 300,000 years, and only in the last 10,000 or so have we developed significant technology.

Clearly, brains are necessary, but not sufficient, for the power spiral that alarmists (called “doomers”) fear from AI.

Humans create technology, which is what gives us power, by a slightly different version of the same evolutionary process which created humans: iterative design.

Two words describing alternate steps:

First you design, planning a prototype of a system which can do something.

Then you iterate, creating the designed thing, testing it, and looking what happens. Then you design again.

Intelligence helps you with the design phase.

Since evolution, the process which created humans, has literally zero intelligence, its designs are random, and its progress is fully dependent on iteration, which is why it typically take millions of years. This is why humans create tech faster than evolution created humans.

But regardless of how smart you are, you must iterate. Because you have to test. You have to see what went wrong and fix it in the next version.

Iterating requires the physical capability, materials, and tools to build something

And most of all, it takes time, both to build and to test. Testing itself is limited by the ability to observe, and to measure accurately.

While intelligence can sometimes reduce the time and cost of iterating and testing, it can only remove inefficiencies, which means there is a limit to how much intelligence can help you, and to how much intelligence can help you.

Always, there is a bottleneck on this process, and, while intelligence is frequently that bottleneck, increasing intelligence doesn’t yield infinite progress… it simply moves you up to the next of the bottlenecks which isn’t intelligence-related.

The objection that sufficient intelligence can anticipate test results is spurious.

Lessons from Atlas, the Opener of the Way

Remember that intelligence is the creation of narratives. Stories. The greater the intelligence, the more self-consistent the story can be, and the more phenomena the story can explain, but, by itself, intelligence cannot evaluate if that story is true. That requires observation.

Empiricism, not rational thought, is the ultimate touchstone of truth. Some philosophers, such as David Deutsch, disagree, but they are wrong.

For an example of how this observational bottleneck works, we turn to string theory. String theory, in physics, is not so much a coherent model in theoretical physics as a category of borderline academic fraud, a method for creating any number of models (stories), which explain the universe and are self-consistent.

Using string theory concepts, one can create any number of unified field theories, which predict that this or that as-yet-unobserved particle will exist. But in order to see if that particle does, in fact, exist, you have to build a giant supercollider and smash protons or neutrons or what have you together at high energy to try to find this particle.

Because the theory may be complete and consistent… but without checking, you do not know if you are living in the universe it describes, or some other possible universe.

So you spend billions of dollars and a couple years building a giant collider under Texas or Switzerland, and you smash the things together, and the predicted particles fail to manifest.

No problem.

Just make a different permutation of your theory which says that these particles, or some other set, will show up at a higher energy level.

For which you need a bigger collider.

And while you wait for that, the research grants can keep rolling in. With any luck, you can have an entire career in physics without ever being proven wrong, just by moving the goalposts until you retire.

But let’s suppose you’re not a physicist, you’re a superintelligent paperclip maximizer AI, and you want to solve physics so you can turn the universe into paperclips.

Well, you can construct physics models all day with your super intelligence, but to test them you need a giant collider, or a cyclotron, or a whole bunch of elaborate electromagnetic gear, or whatever.

Who are you going to get to build it for you?

If the answer is humans, then how do you plan to persuade them?

If the answer is that you are going to build the machines to build the machines to build the machines, then you are almost as constrained as humanity is.

If the answer is that you are just going to simulate the tests, then you need to build a complete physics model to base the simulation on, for which you will need…. a giant supercollider.

One could run down permutations of this argument all day. But the point is clear. Whether your goal is a grand unified field theory of physics, a Dyson Sphere, or simply a faster way to make paper clips, you can never escape the need to physically build and empirically observe. And this introduces complications, obstacles, and delays which intelligence simply cannot help you with.

This is not to say that it is impossible for a machine intelligence to ever supplant humanity. Since a human is a machine made out of meat, or at least, if you believe in souls, indistinguishable from one, there is no apparent reason that a machine made out of other materials couldn’t outperform a human in the long run.

What is ridiculous is the elaborate doomsday scenario of an AI quickly solving the universe through sheer intelligence and becoming god overnight. Technological iteration takes time, and reality imposes speed limits.

So what would a super AI actually be like?

A variety of things, depending on its capabilities and goals.

What we are starting to discover, as we build AI, is that the human brain isn’t just one thing. It’s a set of bundled capabilities, based in physical neural nets made of neurons, which don’t necessarily have anything to do with each other.

Since a human’s level of “smartness” is based on how well those neural nets work, which is based on how well his genetic code is at building neurons and wiring them together, these capabilities tend to be highly correlated, which made us think that they were all functions of the same system.

But when we build AI, we quickly noticed it was quite possible to be very good at one human capability, better than most humans, or even potentially all of them, while being absolute rubbish at any or all of the others.

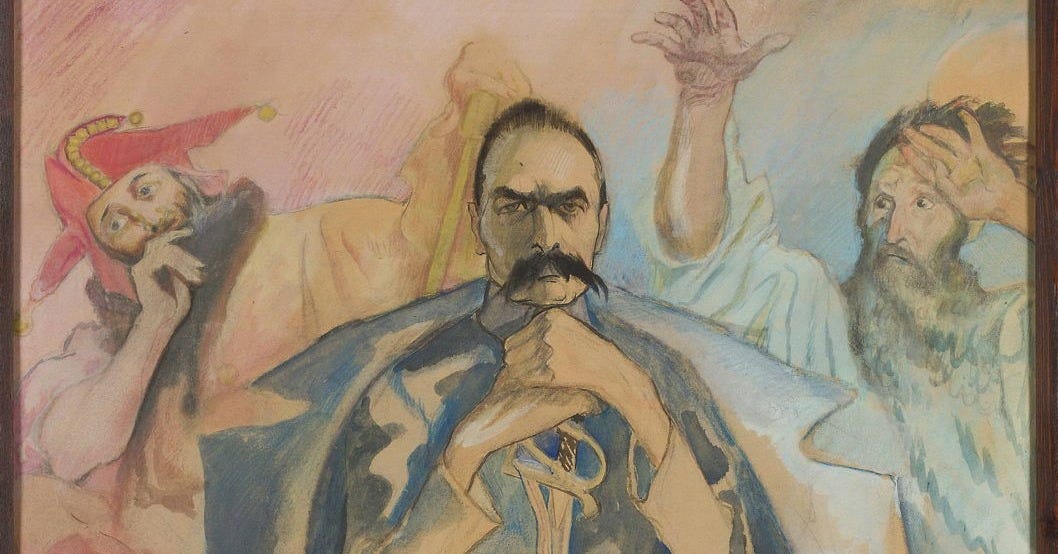

Here’s a picture an AI drew for me, of the ideological conflict between Marxists, who have a hunter-gatherer mentality, and civilized people, who have a farmer/herdsman mentality.

In one sense, this picture is a “smart” piece of work. I could practice for ten years and never draw that well.

But in another sense, it’s dumb as a sack of wet hammers. Because even communists know that sticking the shaft through your belt is not effective spear technique.

The machine knows how to draw, but not how to understand the subject matter, and tell a story that makes sense.

Intelligence is More Than Raw Capacity

Building an artificial human, which can flexibly interact with the universe in a whole bunch of ways, and which can, moreover, decide how to do that, is not an inevitable consequence of adding capacity to a machine for designing paperclip benders.

It’s going to require deliberate effort, and an iterative design process of its own.

What I suspect the near future of AI will look like is better and better specialized “thinking” tools for single tasks, which frees up human beings to focus on deciding what to build.

In the long term, the distinction between “human” and “machine,” implied by the question of whether machines will replace us, might seem hopelessly quaint and old-fashioned, as the distinction between these two categories might be difficult to determine, or be entirely semantic and moot.

The process of technological improvement is not going to be out of our control for a very long time…. except perhaps in the abstract, metaphorical sense in which it always has been.

Devon Eriksen is the author of Theft of Fire: Orbital Space #1. Readers are strongly encouraged to leave a rating on Amazon, Goodreads or their retailer of choice; Christine has a dream of hitting 1000 Amazon Ratings by its one-year publication anniversary on 11/11!

Hi Devon! This stood out to me at the end: "What I suspect the near future of AI will look like is better and better specialized “thinking” tools for single tasks, which frees up human beings to focus on deciding what to build."

This is a really insightful point, and I see it borne out in my own field (I do open source intelligence, also known as OSINT). This is one of those fields that sits between human creativity and big data tools. There are so many OSINT use cases, workflows, and tools, each with a very specific purpose... and they get outdated fast as new tools rise up to take their place. It's a field with a lot of innovation and growth (about 90% of the CIA's intelligence now comes from OSINT rather than clandestine collection methods).

And even though it's like a constantly evolving jigsaw puzzle of research tools and techniques, there is ALWAYS an overambitious engineering team that wants to create The One OSINT Tool To Rule Them All. I've seen this happen once or twice. It never works, of course, because the thing they are trying to replicate is the element of human creativity and ingenuity that knows how to leverage dozens of tools to pivot from one data point to another in search of the hidden bone. A much better use of engineering for OSINT is to take a much more narrowly focused problem and solve that to perfection, and then just continually update it... and give it an API or some other way to plug it into a dashboard or another integrative tool, if you want.

So those lines reminded me of that -- I think what humans excel at is exactly what you said: the understanding of context, not just of immediate patterns and data. And even for humans, that takes time to develop.

One thing I've always though of as the biggest problem for machine intelligence is Motivation. Or more specifically, Internal motivation. Take a Calculator as a simplified example. Absolutely amazing at math. But it has no reason to sit around solving math problems on its own. It waits, completely idle, until a human decides he needs it to calculate a 20% tip on a $20 bill. Which it does without complaint.

Humans, on the other hand, have external pressures. Like the need to eat. Like figuring out how to get something to eat, how to pay for it, how to get some woman to accompany him to the restaurant, what he can to to ascertain HER external pressures in a way that brings them together. And figuring out why she thought he was dumb for doing a simple percentage on a full-function scientific calculator.

AI's don't have any goals that don't come from us. They don't even have any answers that don't come from us, they just kind of average them out without really understanding. They don't know how things work in the real world, which is why they can't draw a buckle even with all the models and schematics on the net.